Childhood Memories With Fethullah Gülen

Childhood Memories With Fethullah Gülen

In This Article

-

I remember running wild around Chestnut Retreat Center when it was a couple of weathered cabins along a dirt road, but as with everything Hizmet and Hocaefendi, there was a vision.

-

I have countless priceless childhood memories, yet the truth is that my connection with Hocaefendi mirrors that of my parents — rooted in his writings and sermons.

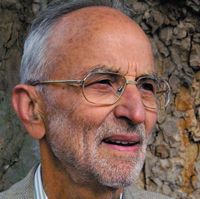

Home means different things to different people. Thirty years ago, I was born in the very place where Fethullah Gülen, known locally as the Turkish Scholar of the Poconos, spent his final moments. I’ll use the term Hocaefendi, meaning esteemed teacher, throughout this article, as that’s how I knew him. He’s the one who taught me the true meaning of community.

My parents moved here from Turkey for higher education and met during their master’s program at Lehigh University. But their story — and mine — truly begins with how they encountered Hocaefendi, whose leadership inspired them to pursue their studies in the U.S.

During her college years in Eskisehir, Turkey my mom attended lecture circles discussing Hocaefendi’s writings and sermons and became captivated by his teachings. My grandmother still recalls having to pull her away from those books to help around the house. Meanwhile, an old uncle in my dad’s village had introduced him to the “Risale-i Nur” by Said Nursi, one of Gulen’s teachers, which led him to people who helped him find housing for college. He was introduced to Hocaefendi’s teachings when asked to become a tutor there. At first, he didn’t understand why — he just wanted to focus on his studies. Neither of them had met Hocaefendi in person. Yet, somehow, his influence was powerful enough to guide them to seek education across the globe in a country they had never been to — long before the age of widespread internet or video calls.

My parents came to the U.S., met, and had me — all thanks to the sermons of a man they had never met. By God’s grace, they met him in the unlikeliest place: Saylorsburg. I’m sure you can guess how many Turks lived here before 1999, so when news broke that he was moving permanently, my parents were honored to help him find his new home. I remember the sweet rush of preparing his room with my mom before Hocaefendi’s arrival.

I was 4 or 5 years old, so my memories are mostly snippets. Still, one is clear: I felt completely comfortable around Hocaefendi, free to be myself, even when the adults always told me to act differently —“Be quiet, stop running around, be respectful.” I was being respectful; I loved my Hocaefendi.

I remember running wild around Chestnut Retreat Center when it was a couple of weathered cabins along a dirt road, but as with everything Hizmet and Hocaefendi, there was a vision.

One day, while he was busy writing in his room, my friends and I were next door, jumping on couches and having the time of our lives — just being kids in full chaos mode. He came out and asked us to settle down, and we did … for as long as a group of unsupervised kids could. Then he came out a second time and a third, this time wearing a stern expression. He lined us up and said he would give us a “ceza” in Turkish. To us, that word only meant one thing: punishment. To our surprise, he handed each of us a $20 bill. We raced down the stairs, nearly giving our parents heart attacks as we exclaimed, “We got a ceza from Hocaefendi!” The candy we bought from the vending machine that day may have been the tastiest we’d ever had.

As an adult, I learned that in Ottoman Turkish, ceza refers to any kind of equivalent returned for something given or done, whether punishment or reward. Throughout my life, I’ve never witnessed Hocaefendi tell a lie, even for the sake of a joke.

I have countless priceless childhood memories, yet the truth is that my connection with Hocaefendi mirrors that of my parents — rooted in his writings and sermons. Throughout my adolescence, college years and moments of crisis, Hocaefendi’s words guided me back home.

Often, I found myself as the only visibly Muslim woman in a room or even in an entire school. Despite this potentially isolating experience, I discovered a sense of community wherever I went. Inspired by his example, I aspired to make everyone I encountered feel as he made me feel — free to be themselves. His teachings allowed me to connect through faith, service and shared purpose, emphasizing the importance of accepting people for who they are, walking with humility, caring with compassion and serving with intention. He gave me a profound purpose: to be the best version of myself that God wishes to witness in His creation.

Now, as I live in Hawaii, completing my pediatrics residency and building a new home community, I reflect on the lessons Hocaefendi imparted. Though I wasn’t able to attend his funeral, I find comfort in knowing that he would encourage me to continue my journey with the same dedication I embrace every day.

In Turkey, it is customary to identify oneself by stating the birthplace of one’s father when asked where they are from. However, for me, I proudly and confidently say I am from Pennsylvania, knowing that it’s a place deeply intertwined with my identity and the invaluable lessons I’ve learned from Hocaefendi.

First published in The Morning Call, November 2, 2024